In my recent book, I provide some explanatory frameworks on the pedagogical uses of VR. While much of the public discourse centres around technical differences between types of VR (i.e. the difference between 3 Degree of Freedom [DOF] vs 6 DOF) or whether 360° technology is ‘real’ VR, as an educator I think it is more important to focus on the pedagogical utility of the technology. One way of making pedagogical sense of VR is to conceptualise its different possibilities for learning with explicit connection to the signature pedagogies of disciplines (or school subjects derived from disciplines).

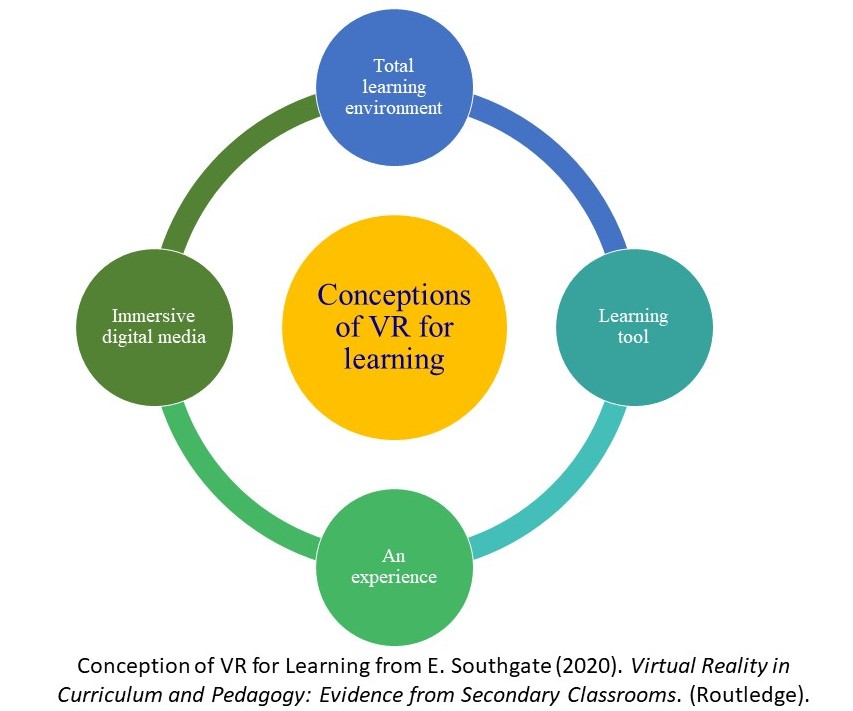

The diagram below (developed for the book) illustrates some key conceptions of VR for learning. VR applications can reflect one or more of these concepts.

When teachers are considering VR they should explore the learning experiences the application offers and how this might fit with the range of instructional strategies commonly used in specific subjects. For example, if you were teaching history you might ask if the software offers a means for transporting students to another place or time because this would fit well with the instructional repertoire usually deployed in the subject area. A core instructional strategy used in a subject is called a ‘signature pedagogy’ (Shulman, 2005). Signature pedagogies are important because they:

implicitly define what counts as knowledge in a field and how things become known…. They define the functions of expertise in a field. (Shulman, 2005, p. 56)

In the case of sparking the imagination through a historical re-creation experience (re-creation being a signature pedagogy of the discipline of history), a time-travel experience would traditionally be facilitated through the instructional use of text, maps, or video. Choosing a time-travel VR experience for history makes good pedagogical sense because it leverages or extends on the signature pedagogy of that particular discipline. Relatedly, this is why VR resonates with the types of place-based pedagogy used in subjects such as geography or in professional training simulations. The technology can be used to take the learner elsewhere and its spatial affordances (properties) fit with the signature pedagogy of geography which is the field trip or professions where situated learning in workplaces (placements) are key (such as clinical health or teacher education).

Let’s look at another example using the diagram. In order to teach science, an educator might want to provide students with the opportunity to conduct experiments that are too complex or dangerous for a school laboratory – experimentation in labs being a signature pedagogy of the discipline of science. The teacher would therefore investigate if there was a total learning environment in the form of a virtual laboratory available so that experiments could be safely simulated.

A performing arts teacher might find that a virtual studio would be a great addition to the actual studio of the drama classroom because it offered a range of tools for her student to design sets and costumes. VR design studios allow for ease of prototyping (click of the controller for creating, erasing and changing elements) at actual scale and let students easily share design ideas for rapid feedback from the teacher and peers (the book has a case study on how a real teacher did this in a rural school). In this case, the virtual environment offers tools to support the signature pedagogy of drama teaching which involve facilitating the creative processes through improvisation and iteration.

Finally, some VR applications enable student content creation – this might be through coding (using game engines such as Unreal and Unity for example) or with more accessible ‘no code create’ drag-and-drop software. In this pedagogical conception of VR, students use the technology as a form of immersive media that can tell a learning story. Students create their own worlds and tell their own stories to demonstrate mastery of learning outcomes and to communicate with, and teach, others.

This pedagogical conception of VR as media informs our latest research on using 360° content creation for second language learning at Athelstone primary school. The 360° platform, VRTY, offers ‘no code create’ opportunities for primary school students to create their own ‘surround’ worlds that acts as a foundation to embed other media into (other media includes gaze-activated pop-up text, sound files, photos, videos, gifs and animations). Students are required to demonstrate that they meet learning outcomes, such as oral or written mastery of Italian vocabulary, by creating a 360°world that is enriched with other digital content they have created. Students can link 360° environments together through gaze-activated portals. The many layers of media content creation entail students planning, experimenting, designing, and evaluating the story they want to tell in their virtual worlds. They then share their creations with peers and the teacher for authentic feedback. They are making media-rich narratives to educate others about the Italian language and culture while demonstrating content mastery.

One our key research questions involves understanding how language teachers can leverage their signature pedagogies to take advantage of the learning affordances of 360° media creation in ways that enhance student engagement and learning. Concentrating on the instructional utility of VR in direct relation to the distinctive pedagogies of the subject being taught – its signature pedagogies – will yield theoretically rich and salient insights for teaching and curriculum design. You are invited to follow our adventure. Stay tuned.

Bought to you by A/Prof Erica Southgate on behalf of the Athelstone School VR School Team

References

Shulman, L. S. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134(3), 52-59.

Southgate, E. (2020). Virtual reality in curriculum and pedagogy: Evidence from secondary classrooms. Routledge.