I recently received an intriguing inquiry asking if there was a standard for measuring the effective use of VR in education? What a thought-provoking question (and I thank my colleague for this because it really got me thinking). It got me thinking that now is the time to disrupt some common assumptions about VR (and XR – eXtended Reality) technology for learning so that we can genuinely work out how to best to use the tech in schools and other formal educational settings.

Reductivist assumptions – reducing the complexity of learning and of learning with VR – are sometimes evident in the field of VR for education. These assumptions will prevent us from understanding the many and varied issues related to designing educational VR applications and implementing these at scale in classrooms, virtual and real. Reductionist assumptions restrict our critical engagement and our ability to imagine possibilities for VR in classrooms. Reductionism is a hasty and lazy intellectual and practical position that seeks to simplify the multi-dimensionality of phenomena (things in the world such as this thing we call ‘learning’). While reductionist accounts of using VR for education can offer comforting and easily digestible ‘answers’ to difficult or intransigent issues, this approach will, overall, act as a roadblock for educators navigating towards use of the technology to realise its creative, cognitive, moral and social potential for humans.

Here are a five reductivist assumptions that need challenging:

Reductivist assumption 1: Learning is recalling facts and figures and VR should facilitate this.

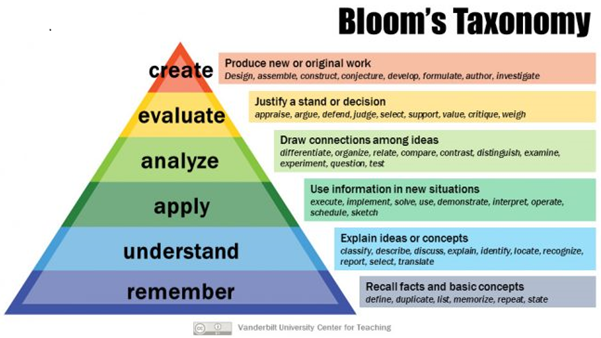

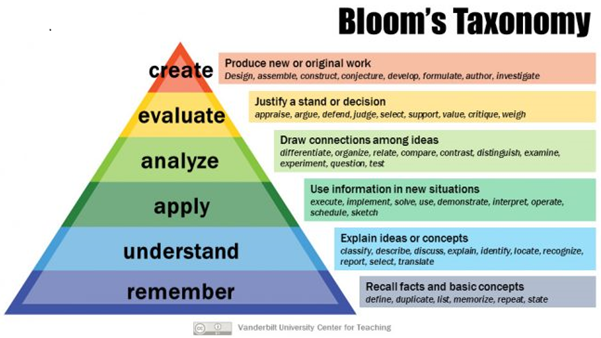

Let’s not reduce the difficult and joyous processes of learning to just recalling facts and figures for a quiz. Sure, declarative knowledge acquisition (recalling facts, figures, data, information – the core stuff of content knowledge) is important. This is why remembering (or recall as educators say) is a foundational cognitive process of Blooms Revised Taxonomy (Figure 1) [1, 2].

Figure 1: Blooms Revised Taxonomy [1]

Researchers often focus on the question of whether exposure to a VR experience can increase recall of declarative knowledge (facts and figures) especially compared to having the same content delivered via a different type of media or through a traditional instructional approach. This type of research is important as it provides a measure of content knowledge acquisition (usually in the short term, unless the researcher re-tests participants to see whether the knowledge has been retained). From a research perspective it is reasonably easy to give a pre and post quiz on facts and figures and compare the results (and perhaps even give learners other surveys that measure factors that might mediate declarative knowledge acquisition such as an individual’s self-efficacy, spatial awareness, motivation etc.).

However, we would be doing ourselves a disservice as educators and researchers if the only type of learning we cared about was recall of declarative knowledge. As Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy points out, we want to know if student understand the implications of what they can remember, can apply it to similar or novel situations (transfer), deploy that knowledge as part of critical analysis and evaluation, and use it as part of a process that creates completely novel perspectives and products.

We require more research on designing and using VR, and other XR tech such as augmented reality, to support learning that includes but moves well beyond the bottom layers of Bloom’s taxonomy. In practice this means examining VR products for their ‘baked in’ or implicit assumptions about what learning is – if applications only promote recall of declarative knowledge with some limited understanding, then that is fine, as long as we recognise this as only one (vital but limited) facet of learning.

We might also ask ourselves why we should make an investment in VR hardware and software if declarative knowledge recall is the only learning outcome from an app especially if this can be achieved through other more ubiquitous, cheaper technology and/or traditional classroom pedagogical practice?

Reductivist assumption 2: We just need a killer VR educational app and the pedagogical use case will follow.

Some technologists like to talk about killer apps (the one app to rule them all) and how it will create the ultimate “use case” (meaning the best way to pedagogically use VR even though they don’t use the word pedagogy). There are also educators who like to flip this and say, ‘pedagogy before technology’. Both positions are naive simplifications.

I’ve said it before, and I will continue saying it – Pedagogically, VR is not one thing.

As represented in Figure 3, we can think of VR as a new form of media that can empower learners through consumption of immersive experiences and some apps allow learners to create their own virtual objects and worlds to demonstrate learning. There are also VR apps that simulate total learning environments such as laboratories or clinical settings.

Figure 3. Conceptions of immersive VR for learning [3]

VR applications can offer diverse types of learning experiences Consider the varying degree of active learning that students can have in different virtual environments (Table 1).

Table 1. Typology of VR environments by student learning interaction and autonomy [3].

We have a long way to go to theorise and explore the many different pedagogical uses for VR and which of these are most suitable for classrooms across age levels, subject areas, and for different types of learning objectives. I hope that there will be a smarm of killer apps that can create a buzz in the classroom and that these reflect beautiful, pedagogical diversity.

Equally, we need to be much more critical in interrogating the pedagogical assumptions that underpin conceptions of instruction and learning in VR apps. It’s no use saying ‘pedagogy before technology’ when VR applications (and other forms of Edtech) already have pedagogical assumptions baked in.

Reductivist assumption 3: VR is the curriculum

VR apps will never be the curriculum – they can never replace the complex and diverse ways that teachers interpret, enact and truly differentiate curriculum in their classrooms. Thinking that a killer VR app will arrive that will replace a teacher’s skillful mediation of curriculum to student diversity is a furphy. What teachers need are VR apps, with real classroom case studies attached to them, that can help them imagine possibilities and enhancements as they plan and implement their interpretation of curriculum for their students. We need to explore how teachers design curriculum that weaves VR apps through it to enhance specific types of learning.

The metaphor needs to be weaving into curriculum not replacing it.

Reductivist assumption 4: We need a standard way to assess learning with VR

Assessing learning with VR will be as varied as its pedagogical uses and the learning objectives that flow from these. Learning is not one thing. Blooms Revised Taxonomy provides a window into the multidimensional cognitive aspects of learning and being clear about the learning objectives when selecting applications is vital. As teachers ask yourself these questions:

Are we using a VR application to assist with declarative knowledge acquisition? Or, to allow learners to develop procedural knowledge and skills they can practice in a VR simulation? Do we want applications that provide opportunities for transfer of existing knowledge? Or select VR environments that can, in-situ, foster ‘soft skills’ such as communication, collaboration, and time-management? Does a VR app assist with developing affective or moral learning related to empathy or examining belief systems, for example? Are we looking to provide opportunities for learning that involve verbal and non-verbal communication with others for (inter)cultural understanding and exchange? Or, to provide a virtual forum that gives students an opportunity to meet experts who can share their wisdom in dialogue and action? Do we want to use VR applications that can fire up the imagination to promote creativity and the exchange of creative processes and products? Or select VR environments that give students access to unique artistic, intellectual, cultural or sporting events?

Just as VR is pedagogically not one thing, its potential nexus with the varied types of learning and learning objectives creates a rich educational tapestry. For each of the types of learning listed above, the teacher would identify or develop assessment criteria with metrics and non-quantifiable means of determining if learning objective/s had been met, and the role of VR in this.

While commercial VR is a young technology in formal educational contexts such as schools, we have reached a point where we need to complicate our conception about learning with the tech including our approach to assessment, not simply it.

Reductivist assumption 5: Hardware choices are technical choices

Hardware choices are difficult. In schools we are talking about investment of precious resources with an evolving yet not established evidence base on pedagogical models and efficacy for learning with VR. Hardware choices are not however only technical choices. The hardware, platform and software that teachers choose will have ethical implications for their schools and classrooms.

This is a space filled with tensions and unknowns when legally and ethically it should be clear to educators, students and their families exactly what data is being collected, harvested in real-time and shared/sold-on by tech companies whose VR hardware, software and integrated platforms are being used in classrooms. Artificial intelligence can automatically harvest vast amounts of highly identifiable biometric data (information about individual bodies such as gaze patterns and pupil dilation, movement, proximity to virtual objects, voice etc). Is this data being collected, for what purposes and with what consent? Camera built into VR headsets can capture the real environment that students are in – what implications does this have for privacy?

Manufacturers of hardware usually put an age limit in their online safety advice, and it would be wise for teachers to check this too before procurement. Educators should also be aware that social VR, while opening the world up to learners also has child protection issues.

Many countries have weak regulation regarding data harvesting and the selling-on of such sensitive data including biometrics, which is usually gathered without us knowing. It is up to teachers to think ahead on these types of ethical issues and make fully informed, justifiable procurement decisions. I know this is a difficult job and puts educators in a quandary, but technical choices in this field are also ethical choices.

FYI – The Voices of VR podcast frequently covers privacy in XR – https://voicesofvr.com/

This post is bought to you by A/Prof Erica Southgate.

References

[1] Vanderbilt University (n.d). Blooms Taxonomy Diagram. Retrieved https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/

[2] Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into practice, 41(4), 212-218.

[3] Southgate, E. (2020). Virtual reality in curriculum and pedagogy: Evidence from secondary classrooms. Routledge.

Cover photo by Rodion Kutsaiev: https://www.pexels.com/photo/white-and-brown-round-frame-7911758/

“I have developed a Semester-long course for my Year 9 Digital Design class using VR as a form of new media for students to demonstrate knowledge about sustainability and to educate others in the school community about this. The learning outcomes from the

“I have developed a Semester-long course for my Year 9 Digital Design class using VR as a form of new media for students to demonstrate knowledge about sustainability and to educate others in the school community about this. The learning outcomes from the

Adrian Stenta (left), teacher and co-researcher on the VR project, developed a

Adrian Stenta (left), teacher and co-researcher on the VR project, developed a